The Bugatti EB110 showed the way for future hypercars

For well over a decade, the Bugatti EB110 remained almost as unknown as if it had never existed.

Bugatti closed its doors for the second time in 1995, so the EB110 spent the rest of the 1990s at the top of an empire found only in history books. With no direct successor to pass its torch to, the wedge-shaped coupe once celebrated by Michael Schumacher as the supercar to tame them all faded from the car world's collective memory, even though some of the records it set remained unbroken.

Its star began to rise again during the 2010s thanks to 1990s nostalgia, or because enthusiasts realized 21st-century Bugatti models owe more to the EB110 than to the pre-WWII Type 57. Either way, it's finally accepted as an influential part of the Bugatti story. Its unusualness adds to its mystique; it was manufactured in Ferrari's sun-dried back yard, yet it propelled the French company into the modern era.

Italian entrepreneur Romano Artioli knew the automotive industry well before he purchased the rights to the Bugatti name in 1987. He had built his vantage point on decades of experience. He owned one of the first Opel dealerships in Italy, he later became the country's official General Motors importer, and he also distributed cars for Ferrari, among other automakers. He enlisted some of the most respected engineers and designers to help him relaunch Bugatti while honoring its tradition, but he made one significant exception.

Bugatti's roots are in France, in a picturesque small town near the border with Germany named Molsheim. Alsace is better known for sauerkraut than supercars, so he decided to base the born-again automaker in a town called Campogalliano located on the outskirts of Modena, Italy. Setting up shop a stone's throw from the headquarters of Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati, and De Tomaso allowed him to tap into the Motor Valley's deep pool of suppliers and workers well-versed in high-end cars as he assembled the pieces needed to create the first new Bugatti since 1956.

Right away, Artioli wisely decided to begin the project with a blank slate instead of borrowing a chassis, an engine, or both from another company. He felt Bugatti needed to be an automaker, not a coachbuilder or a purveyor of kit cars. Early EB110 prototypes were built on an aluminum chassis, and they wore a body designed by Marcello Gandini of Bertone fame. When Gandini spoke, everyone listened and no one dared to contradict him. Artioli was unfazed and unimpressed boldly rejecting the first prototypes because they were too heavy, and they didn't look the way he wanted them to.

With aluminum out of the picture, Bugatti's nascent research and development department worked closely with Aérospatiale, a French state-owned airplane and helicopter manufacturer which later merged with Airbus, to create a carbon fiber monocoque that lowered the EB110's weight to approximately 3,500 pounds. With Gandini out of the picture, the design took a less angular direction fine-tuned by Giampaolo Benedini. His involvement was more than a little surprising because he wasn't a car designer; he was the architect who penned the blue factory the EB110 came to life in.

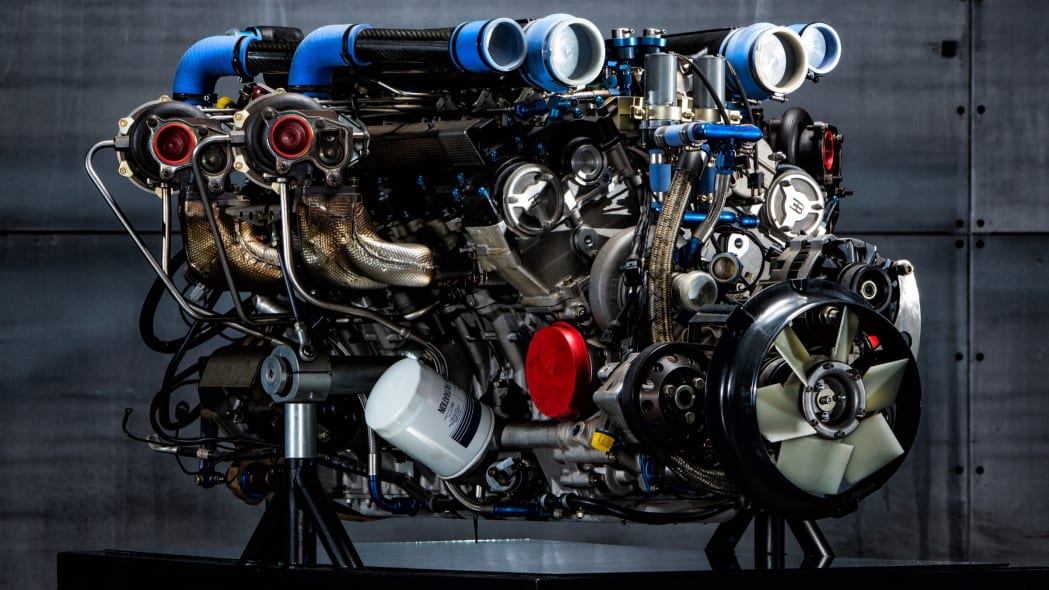

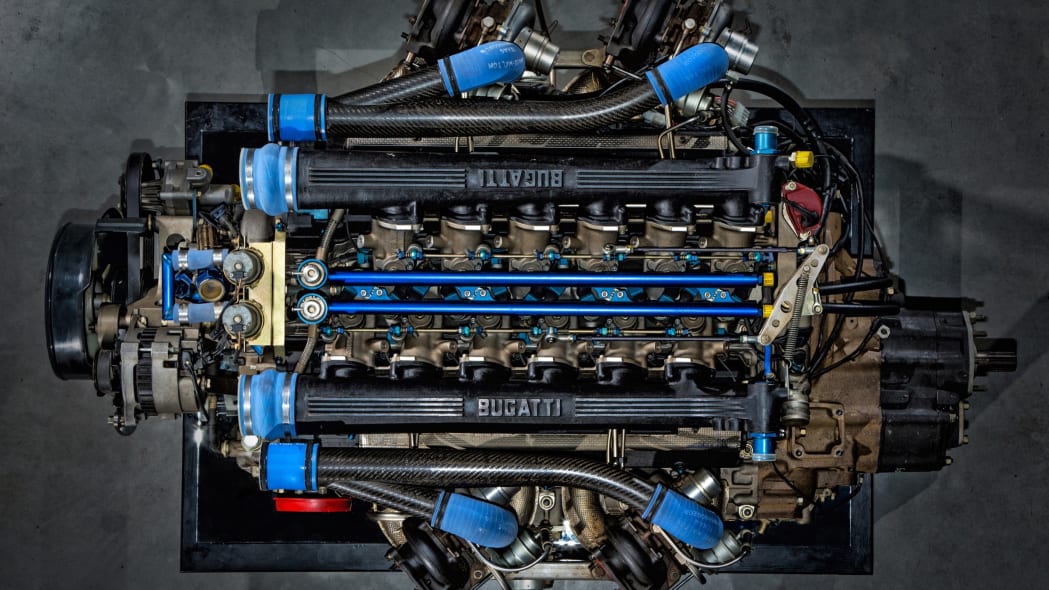

Meanwhile, a team of engineers including Paolo Stanzani, Oliviero Pedrazzi, and Achille Bevini worked tirelessly to make Artioli's vision of a mechanical masterpiece a reality. These men had played a starring role in developing a long list of poster-worthy supercars ranging from the timeless Lamborghini Miura to the short-lived Cizeta-Moroder V16T. Initially working out of a small garage near Modena, they created a 3.5-liter, 60-valve, quad-turbocharged V12 that delivers 560 horsepower at 8,000 rpm and 450 pound-feet of torque at 4,200 rpm. Those figures were nothing short of breathtaking during the early 1990s. To add context, the Ferrari F40 that the automotive world worshipped as the supercar segment's headlining act offered only 471 horsepower from a twin-turbocharged, 2.9-liter V8.

The EB110's mighty 12-cylinder channeled its power to the four wheels via a permanent all-wheel drive system and a six-speed manual transmission. Bugatti conservatively quoted a 3.3-second sprint from zero to 62 mph, and 212-mph top speed. And yet, the EB110 wasn't a barebones track car. The standard car offered air conditioning, power-operated seats, and a generous layer of sound-proofing material, among other comfort-focused features, to let owners effortlessly cruise across countries. In hindsight, it set the mood for the Veyron and its successor, the Chiron, which Bugatti still makes in 2019.

EB110 production began in 1991, and the supercar quickly drew the attention of the world's wealthiest motorists. Bugatti knew some buyers would want a more hardcore car, so it released a more track-focused variant of the EB110 called SS about six months after the standard car – which wore the GT suffix – made its debut. It used the same basic 3.5-liter V12 but its output increased to 611 horsepower at 8,250 rpm and 480 pound-feet of torque at 4,200 rpm. It's this variant that Bugatti used to set records around the world. After all, superlatives are important in the supercar segment.

On May 29, 1993, the EB110 SS reached 218 mph on the Nardò track in southern Italy. On July 2, 1994, an experimental EB110 equipped with an "Ecogas 2000" system – that is to say, powered by compressed natural gas and tuned to a claimed 650 hp – topped out at 213 mph on the same track. On March 3, 1995, the EB110 became the fastest car on ice by reaching 183 mph near Oulu, Finland; this record stood until 2007. An EB110 SS with 670 horsepower participated in the 1994 edition of the 24 Hours of Le Mans, but it slowed down after experiencing turbo problems, and ultimately dropped out of the race after skidding into a wall on the Mulsanne Straight due to a tire blowout.

Records and racing play a significant role in forging an automaker's image, but they can't keep it afloat. Artioli needed scale, and he couldn't find a bigger automaker to join forces with, so he began forming his own automotive empire by purchasing Lotus from General Motors in August of 1993. The move made sense: in time, his group would have a presence in nearly every sports car segment, and it could survive a downturn in the global automotive industry by leveraging its vast engineering expertise.

For Bugatti, Artioli planned a follow-up to the EB110 named EB112. Presented as a concept at the 1993 Geneva Motor Show, it took the form of a big, stately sedan with a fastback-like roof line and a naturally-aspirated, 6.0-liter V12 engine mounted in front of the passenger compartment. It was tuned to deliver 460 horsepower. For Lotus, he envisioned a small, accessible sports car that followed the light is right approach to design pioneered by founder Colin Chapman. Developing two specialty cars from scratch is a massive undertaking, and Bugatti's financial problems caught up with it before the Giugiaro-designed EB112 entered production. The Lotus project spawned the original Elise, however.

Bugatti closed its factory in Campogalliano hours after it filed for bankruptcy in September 1995. All told, the plant made 128 examples of the EB110 – including a pair of race cars – by hand. The company's archives department notes it built about 96 cars to GT specifications, and approximately 32 cars in SS trim. German boutique automaker Dauer purchased the unfinished cars on the assembly line from Bugatti's liquidators, plus the firm's complete stock of spare parts (including engines and chassis), and made about nine additional cars in the early 2000s.

Once the dust settled, the EB110 became a mechanically impressive but historically obscure testament of the brand's short Italian period. The collectors that admired it weren't interested in putting one in their garage; prices hovered around the $200,000 mark during the late 2000s. As it ages, the EB110 is finally starting to earn the respect (and the value) it deserves. An exceptionally clean, low-mileage SS shattered RM Sotheby's pre-auction estimate by selling for $2.3 million during Retromobile 2019. We think it's just getting started, and Bugatti's ongoing success will continue to send EB110 prices up.

Nouvelles connexes