Outside the Box: Carlos Ghosn on his escape from Japan

Global tycoons are rarely strangers to risk, but no chief executive has made a bet as epic as the one Carlos Ghosn made last December.

The former boss of the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance did something that he knew would mean he would either live the rest of his life as a free man or die in prison. Despite being under house arrest on financial misconduct charges involving nearly £80 million, he fled Japan as a stowaway on a midnight private jet. "It was a huge risk," he says with surprising dispassion.

It's 9.30am in central Beirut and the world's most famous fugitive is talking to me as he crosses Abdel Wahab el-Inglizi Street and walks into the Hotel Albergo with his wife, Carole. It's one of the few hotels in the city that's still open after the vast explosion in the port in August. Ghosn's nearby home was damaged in the blast but, to him, the battered city is paradise. "I can be with my wife, my kids, who I thought I might never see again," he says, smiling.

Ghosn, who transformed Nissan from a struggling rival of Toyota and Honda to a worldbeater that built the UK's largest car plant in Sunderland, was arrested in November 2018 and charged with under-reporting tens of millions of pounds in earnings. He denies the charges. He was held in solitary confinement in a freezing cell in Tokyo for 130 days and then under house arrest. But last December, the 66-year-old escaped on a private jet to Istanbul and then another to Beirut. It was both the business story and the crime story of the decade.

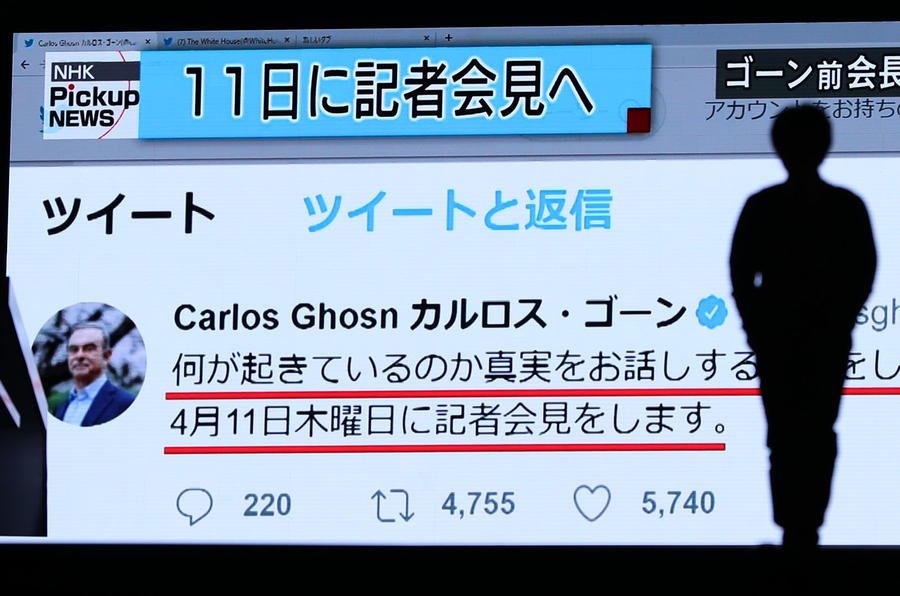

Safely back home (Lebanon doesn't have an extradition treaty with Japan), he's ready to tell his side of the story. "I'm fighting for my reputation," he says, his eyes suddenly as bright as his cornflower-blue shirt. He has written a book, Time for the Truth, in which he accuses Nissan of fabricating the charges against him. He claims that the company wanted to oust him to prevent him from giving Renault greater power in the alliance, a move that would have been too great a blow to Japanese corporate and national pride, he says. What we now know for sure, though, is how he pulled off an escape act that makes Houdini look like an amateur.

Ghosn reveals that, contrary to reports, he himself didn't spend months planning his midnight run. He knew that associates were plotting to spirit him away, but he didn't know the details. He decided to risk it all only last December, after judges refused his requests to see Carole and ruled that his trial would be split into two parts, which meant it would last at least five years. Facing up to 15 years in prison if convicted, "I had to make a choice: live a miserable life of injustice – or take a chance?"

To have any chance of success, the escape "had to be quick and confidential... I restricted my exchanges to the strict minimum." Exchanges? How could he communicate with the escape team when he had no computer and his phone was tapped? Ghosn confirms he had obtained an untraceable 'burner' mobile phone of the kind used by spies and drug dealers. How did he get it? He won't say, but a source close to the operation explains: "If you pay the right amount, you can get anything you want in the Japanese market."

Then a man who speaks four languages at a usual million miles an hour clams up completely. "We're not going to talk about the details." There's a good reason. While the plot worked out spectacularly well for him, it has proved disastrous for his accomplices, Michael Taylor, 60, and his son Peter, 27, from Massachusetts. Michael is a former Green Beret whose speciality is exfiltration – bringing home people caught in a jam overseas. (Think Ben Affleck in Argo.)

The pair were arrested by US authorities in May at the request of the Japanese government, which is seeking their extradition. They face four years in jail if convicted in Tokyo of aiding and abetting a fugitive. Most of the details of the escape have, however, emerged via Beirut sources contacted by The Sunday Times, lawyers and an interview Michael gave to Vanity Fair before he knew the Japanese were closing in on him and his son.

As the first person to have run two Fortune 500 companies at once, Ghosn is as well connected as any man on the planet. As soon as details of his harsh treatment during his time in Japan's Kosuge prison emerged, Beirut sources say the business leaders and backroom fixers who grease the wheels of corporate and political life in the Middle East, where more deals are done under the table than over it, began plotting to, as one put it, "bring our brother home".

A Lebanese businessman, who remains unidentified, contacted Taylor, whom he had met in Iraq when he had been scoping out investment opportunities after the fall of Saddam Hussein and Taylor had been providing security services. He asked if Taylor could "help a friend in Tokyo".

It didn't take Taylor long to figure out what the businessman meant and even less time to realise it would be the toughest job he had ever undertaken. Ghosn was now under house arrest in the city, but his home was monitored by CCTV cameras and plain-clothes detectives followed him everywhere.

Flying was the only option; the nearest western country without an extradition treaty with Japan was more than 2500 miles away. But Ghosn's name couldn't appear on the passenger list and no one could see him board. One of the most recognised men in Japan had to be invisible. Beirut sources say Taylor began studying the layout and security arrangements of every private airport terminal within 300 miles of Tokyo. Osaka's Kansai airport, it turned out, didn't have X-ray equipment big enough to scan large cargo boxes.

Taylor reckoned a box of the kind musicians use to transport heavy stage speakers would be perfect to conceal Ghosn, who is small but weighs 75kg. Taylor told Vanity Fair he asked a staging company in Beirut to build a black box that would be too big for Osaka's scanners but small enough to pass through the cargo door of a private jet. Breathing holes were drilled in the bottom (to disguise them) and strong, quick-rolling casters added. When you're on the run, speed matters.

Next, Taylor needed an aircraft operator who would look the other way on the Istanbul-to-Beirut flight, which Ghosn would have to board normally. The private air terminal at Istanbul's Atatürk airport does scan cargo of all sizes. He asked hundreds of charter companies whether they could handle a "principal" who required "a high level of discretion" – code for a "dark" flight. He had all but given up when Beirut sources say he made one last call to a Turkey-based operator called MNG. An employee said it could help. MNG would later say it had been duped into carrying Ghosn by a rogue staff member.

Taylor had a plane, an airport and a hiding place but still no idea how to get his famous stowaway to Osaka. He got lucky. Through Tokyo sources, he discovered that, inexplicably, the CCTV footage from Ghosn's home wasn't monitored live but examined a few days later. It was all the time he needed to spirit him away, but could it be true? Could they also shake off the plain-clothes goons? It was a risk worth taking.

At midnight on Friday 27 December, Ghosn was in bed at home when his burner phone rang. "I'll see you tomorrow," Taylor said and named the rendezvous point and time, then hung up. Taylor flew into Osaka overnight on a Bombardier Global Express private jet from Dubai. He was with another man, a Lebanese "fixer" who told the pilots to refuel on landing then be ready to leave for anywhere within the jet's 7000-mile range at one hour's notice.

When the cargo was being unloaded, Taylor told the baggage handlers who removed the heavy box, which had real speakers inside, that he was working with musicians who were performing that evening. He had even bought tickets to a local gig in case anyone asked.

At 2.30pm on Sunday 29 December, Ghosn left home and walked to the Grand Hyatt, where he was allowed to go for lunch, but instead of heading for one of the hotel's restaurants, he took the lift to room 933, which had been booked under Peter Taylor's name. Michael and the fixer were waiting for him. He changed clothes and put on a cap, glasses and a surgical face mask (common in Japan even pre-pandemic). The three men left by a side entrance. They couldn't be sure, but didn't think they were followed.

They drove to Tokyo's main railway station and boarded the 4.30pm bullet train to Shin-Osaka Station. With the new year looming, "there were dozens of people in the carriage", Ghosn writes in his book, but nobody recognised him. From Shin-Osaka they drove to the Star Gate Hotel, where Taylor had booked a room. There, while Taylor scrambled the pilots, Ghosn climbed into the box, from which the speakers had now been removed. Taylor locked it and he and the fixer pushed it out of the hotel room and wheeled it to a waiting black van.

Michael Taylor deliberately timed his arrival at Kansai's private jet terminal to be only 20 minutes before the scheduled departure time of 10.30pm. He told staff at the terminal that the concert had finished late, brandishing his crumpled ticket stubs. He was gambling that officials at the end of a long shift would be keen to wrap up and go home. He was right. Security staff waved the music box concealing Ghosn through the terminal and onto a conveyor belt leading up into the Bombardier's cargo hold, situated just behind the passenger cabin. As Ghosn heard the whump of the cargo door closing and the engines firing up, he began to relax for the first time in more than a year. "The noise was the sound of crazy hope," he writes. Shortly after 11pm, when the jet levelled off at 39,000ft at 600mph on "the long way" to Turkey over Russia (the usual shorter route would cross countries that have extradition treaties with Japan), Taylor opened the door from the main cabin to the cargo bay. He unlocked the box and Ghosn eased himself out. There were smiles, but it was too early to celebrate; the riskiest part of the journey was still to come.

The aircraft landed in Istanbul at 5.26am on Monday 30 December. The plan was for Ghosn to walk across the Tarmac and on to a second private plane, a Bombardier Challenger 300, destined for Beirut. Taylor and the fixer would take a later commercial flight to Lebanon. Ghosn felt confident he wouldn't be spotted. The sun hadn't yet risen over the Bosphorus. But he had no way of knowing whether the Japanese authorities had rumbled him. He had been gone almost a day by now. Could they have tipped off the Turkish police? Would the second jet even be there? Ghosn smiled with relief as he spotted the Bombardier. Sucking in the freezing dawn air, he walked over, up the steps and asked the flight attendant to "close up and go".

Looking back now, those close to the operation think the subterfuge at the Grand Hyatt 20 hours earlier might have been unnecessary. Detectives probably hadn't followed Ghosn from his house that day. "No one expects much to happen over new year in Japan," says one. "I wouldn't be surprised if they didn't bother to turn up that day. Japan isn't as disciplined as people think."

Little more than an hour later, at 6am, the jet with no passengers (officially) dipped low over the Mediterranean and bumped to a halt at the VIP Pavilion on the northern edge of Beirut's Rafic Hariri airport. Ghosn, who had changed into dark trousers and a dark jacket, reached for the French passport the Japanese authorities had allowed him to keep in a pouch with a special security seal. He opened it only after landing in Beirut because he feared an electronic warning signal might be sent as the seal was broken. As he stepped out, gazing up at the snow-tipped mountains above his home town, he told himself: "Finally, it's won."

At 6.10am, Carole, who was visiting her parents in Lebanon and staying at her and her husband's house in Beirut, was woken by a phone call from a friend. "Go to your parents' house immediately. We have a surprise for you," he said. She recalls: "My first thought was: 'Oh my God. It's bad news. Who calls at 6am?' " When Carole first saw Carlos stepping out of a black Mercedes with blacked-out windows, she ran to him and "hugged him tighter than I have ever done". Ghosn told her: "You're my lioness. You fought so hard for me."

Ghosn and some of those close to him are reported to have paid almost £800,000 to Promote Fox, a company linked to the Taylors, for their pains. The whole operation might have cost several times that figure. He also forfeited his £11 million bail. Even so, the flight was the bargain of the century. It was a very happy new year. "Beyond happy, a miracle!" Carole laughs.

Not everyone wins

What happened to Michael and Peter Taylor? They could soon find themselves shuffling into a Japanese courtroom in prison jumpsuits. They checked before hatching the Ghosn escape plot that they wouldn't be violating any US laws but didn't investigate whether they might have a case to answer in Tokyo. A federal magistrate in Boston approved Tokyo's extradition request in September. The Taylors have appealed. Does Ghosn feel guilty that they face the prospect of the very jail time that they helped him to avoid? "No comment," he replies.

Nouvelles connexes