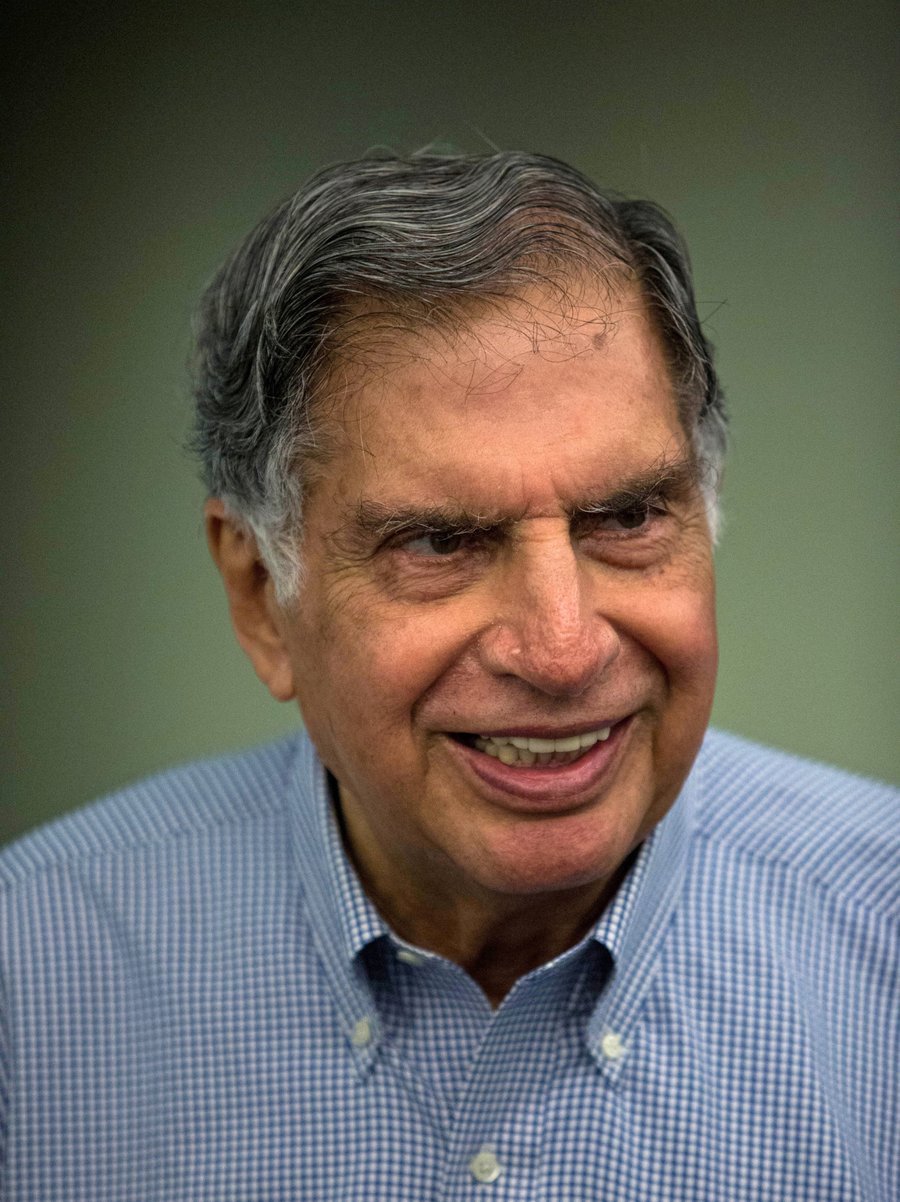

Ratan Tata, Unbridled at 78, Meets His Young Self In Startups

Even after he became chairman in 1991, it was an uphill battle to steer the behemoth into new ventures, Tata told a forum of business leaders in Singapore on Tuesday. When he started the Nano affordable-car project, some employees concluded their stubborn techie leader had lost his mind.

Now, the 78-year-old is free from the shackles of a business that he turned into a global conglomerate, he’s rediscovering his younger self. Since he retired in December 2012, he’s been devoting himself to startups, using his rock-star status to become India’s most famous venture capitalist.

Many of the enthusiastic entrepreneurs he meets and backs remind him of when he was a young man who wanted to make a difference by breaking new ground.

“There was an in-built frustration that carried through most of my career,” Tata told the forum. “Interaction with startups is so exhilarating to me because it allows me to relive that kind of freshness.”

Indian Icon

Tata’s rise as an iconic Indian business leader paralleled the country’s own emergence on the world stage. He transformed Tata Sons Ltd. into a $100 billion global powerhouse, with products from Land Rover cars to Good Earth tea, leading other Indian businesses like Bharti Airtel Ltd. and Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd. to also expand abroad.

Now, some of that growth is in jeopardy, caught by China’s slowdown. Tata Steel Ltd. said this week it’s looking to sell its U.K. steel business that Tata bought for $12 billion a decade ago. Several quarters of losses and 2 billion pounds ($2.8 billion) of writedowns have left the division with an asset value of almost zero.

And while Tata Motors Ltd. is cashing in on the success of Jaguar Land Rover Ltd., the Nano has been a commercial disappointment, hit by bureaucratic red tape that delayed a dedicated factory for two years, and tarnished by an image as the world’s cheapest car.

Those frustrations during his half-century career at the family business surfaced in a talk that followed the hour-long meeting in Singapore with 29 founders of startups backed by Jungle Ventures, where he serves as a special adviser.

“In the corporate world, there is a tremendous amount of control,” he said. “In the new world, no one is asking you, ‘Who’s tried this before? Who’s succeeded in this? Are you sure you can make it happen?’ That’s the kind of change that exhilarates me when I interact with a startup.”

‘Free Agent’

Since his retirement, he’s invested in more than 25 ventures, including mobile payment venture Paytm and Teabox, a premium tea retailer.

“When I retired, I was a free agent. It was my pocket, my money that was used,” said Tata. “So I went into that with a manner of freedom.”

Veterans like Tata bring knowledge and networking to startups, said Arcot Desai Narasimhalu, director of the Institute of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Singapore Management University, which has helped foster 150 startups, including Teabox. “It’s a fantastic opportunity for entrepreneurs who are fortunate enough to have gotten his attention.”

After graduating from New York state’s Cornell University with a bachelor’s degree in 1962, Tata returned to India and joined the family company, Tata Industries, on the advice of his uncle, J.R.D. Tata, whom he succeeded as chairman in 1991.

Land Rover, Tetley

Over the next two decades, Ratan Tata propelled the conglomerate onto the world stage by making multibillion-dollar acquisitions to add global brands such as Land Rover, Jaguar and Tetley tea. Today, Tata group has more than 100 companies and operates around the world.

Yet the lifetime bachelor counts the Nano car project, which started in 2003, as the highlight of his career.

“My colleagues in the car industry overseas said, ‘You know, we tried this and it doesn’t work. Don’t waste your time’,” Tata said. “The most exciting moments in my life were the development of the Nano -- to see it come to be.”

He has a simple strategy in selecting startups to invest in: great ideas and founders who are willing to stick with the business and expand through ingenuity and innovation.

The barriers to entry have come down, and the era where ideas can blossom into new businesses has arrived, Tata said. The “glorified valuations” of some startups will inevitably come down and many ventures will fail before a small number of enormous successes emerge, he said.

And what advice would Ratan Tata give to his 18-year-old self?

“I started my career in a traditional set of companies. People considered that to be a good place to work, but not one that led to innovation,” he said. “If I were that young Ratan Tata, what I would have enjoyed most is somebody saying that we provide you an environment that is more open.”