Risk of Cyber-Threats May Increase as Cars Load up on Computers, Active Controls

New technologies like park assist, adaptive cruise control and collision prevention are some of the first to hold an active role in driving. But because these features are specifically designed to, at times, exert control over a vehicle, it may be easier for hackers to write codes that carry nefarious intent, a first-of-its-kind study recently found.

"Attacks are likely easier in their presence than in their absence," wrote Chris Valasek and Dr. Charlie Miller, the authors of the report, A Survey Of Remote Automotive Attack Surfaces.

There's been no documented cyber attack on an automobile in the United States. But as automakers have rushed in recent years to add software that essentially turns cars into mobile computers, the industry and federal regulators have paid more attention to the potential consequences of a vehicular security breach. On Tuesday, David Friedman, administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, asked automakers to collaborate on ways to thwart cyber threats.

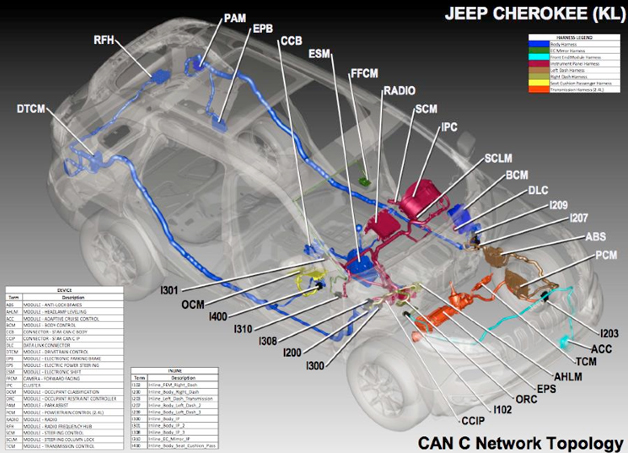

Valasek and Miller, who presented their study last month at a convention of hackers, security analysts and researchers in Las Vegas, NV, offer the first public look at the underpinnings of the network architectures that govern how all these new components are connected.

Their conclusions on 21 individual vehicles are interesting on their own merits; indeed, lists of "most hackable" and "least hackable" cars spawned the initial wave of headlines sparked by the study. What's more notable, in retrospect, is its overall undercurrent. In response to consumer demand for infotainment and advanced safety features alike, automakers are adding software and computer components to cars at a rapid pace. At least for now, much of this technology leaves more questions than answers.

"Transparency in the auto industry isn't that great," said Valasek, who paired with Miller (both interviewed in the video above) on earlier research in which they demonstrated how to manipulate critical control functions on a Ford Escape and Toyota Prius. "It's still, 'Let's keep this a secret.' ... When we originally did it, it was, 'Don't worry, we have super-secret stuff to protect you.' Right now, we get the impression that they (automakers) may be working on it."

Valasek is the director of vehicle security research at IOActive, a computer security company. Miller is a former National Security Administration computer security researcher who now works for Twitter.

In their previous research, the pair had a physical connection to the two cars, and sat in the rear seats while they manipulated brakes, steering and throttle inputs. Their current research is significantly different, Valasek emphasized, in that they didn't physically examine the cars; they conducted an overview of the networks based on mechanic's information collected from each manufacturer. They chose the cars involved in the recent study, in part, depending on whether they had access to that information.

Automakers have routinely been tight-lipped about their efforts to address cyber threats. Chrysler executives, whose 2014 Jeep Cherokee was named the "most hackable" vehicle in the study and whose '14 Dodge Viper was the "least hackable," declined to discuss the findings. In a written statement, a spokesperson said, "Chrysler will endeavor to verify these claims and, if warranted, we will remediate them."

At the root of the challenge for Chrysler and others: manufacturers have expanded the number of electronic control units that govern these features, which run the gamut from seat-belt tensioners, to airbags, to brakes. The number of ECUs on cars has exploded. For example, the 2010 Range Rover contained 41. The '14 Range Rover contains 98 ECUs, according to the study. There were 23 ECUs on the 2006 Toyota Prius; there are 40 on the latest model.

Each ECU is its own miniature computer that comes with a unique set of tasks and vulnerabilities. So the more ECUs on the car, the more risk increases. And the entire system is only as strong as the weakest link.

"They have different costs, but all of them need to be secure," said Walter Buga, CEO of Arynga, a San Diego-based company that makes software for vehicles. "You can have everything super-secure, but one part can compromise everything in the car, including safety."

Researchers from the University of Washington and Cal-San Diego were the first to successfully discover these breaches. In a landmark 2010 study, they found it was possible to hack a car either via physical or wireless access by targeting certain components that sought external signals.

Not every automotive cyber attack is the same. Scenarios can range from mischief, like eavesdropping on a conversation via a telematics unit, to a major attack like injecting malicious code that tampers with brake, throttle and steering control.

The former might only require an attacker gaining remote access to a vehicle with a wireless signal that targets a responding ECU. But the more dangerous scenarios would require at least one more step – injecting malicious code into the internal network in an attempt to influence safety-critical ECUs. Because the newer ECUs have roles in actively controlling some functions, "we assume those with advanced computer controlled features are more susceptible since they are designed to take physical actions based on messages received on the internal network," the study says.

Next Problem: Web Browsers In Cars

Increasingly, Valasek and Miller believe the telematics units that control infotainment are the biggest cyber threats, even if they don't necessarily reside on one of these networks.

"We consider it to be the holy grail because of its range," Valasek tells Autoblog. "Because if you have cellular communication in your car and there was to be an issue – not that we've found any yet – you have the range of almost anywhere, because they're designed to work with the infrastructure we have. That range makes it the holy grail, as opposed to something like Bluetooth."

Those risks are growing. Telematics units control many of the systems that interact with drivers, like touchscreens, radios and GPS units. In some cases, automakers are adding web browsers to these infotainment packages, hoping to lure buyers who want a car to function like their other Internet-connected devices. The problem: hackers have long known web browsers; the technology is relatively new to automakers.

"We've proven we can't write a secure web browser," Valasek said. "So I wouldn't say we're capable of writing the perfect software for an automobile."

Nouvelles connexes