Under the skin: How Kia is keeping the manual gearbox alive

Kia's Intelligent Manual Transmission (iMT), with its clutch-by-wire system, set the antennae twitching at Autocar Towers, because the crystal ball had been revealing only automatic and semi-automatic gearboxes as the solutions to staying on top of future emissions regulations. Clutch-by-wire is an electronically controlled, electrohydraulic clutch actuation system that's specifically designed to work with 48V mild-hybrid powertrains.

One of the problems powertrain engineers have faced, ever since emissions became a thing, is the driver. No matter how skilled they are, drivers aren't good at getting the best efficiency out of an engine and gearbox, and that's why the 'integrated powertrain' approach evolved, with engines and automatic gearbox control systems linked so they can achieve the best economy.

That's all very well for more expensive cars, but for smaller, cheaper cars, autos can be a pricey overhead. Clutch-by-wire bridges the gap, allowing a manual gearbox to gain an added economy feature, namely coasting with the engine shut down. So far, this has only been possible with autos.

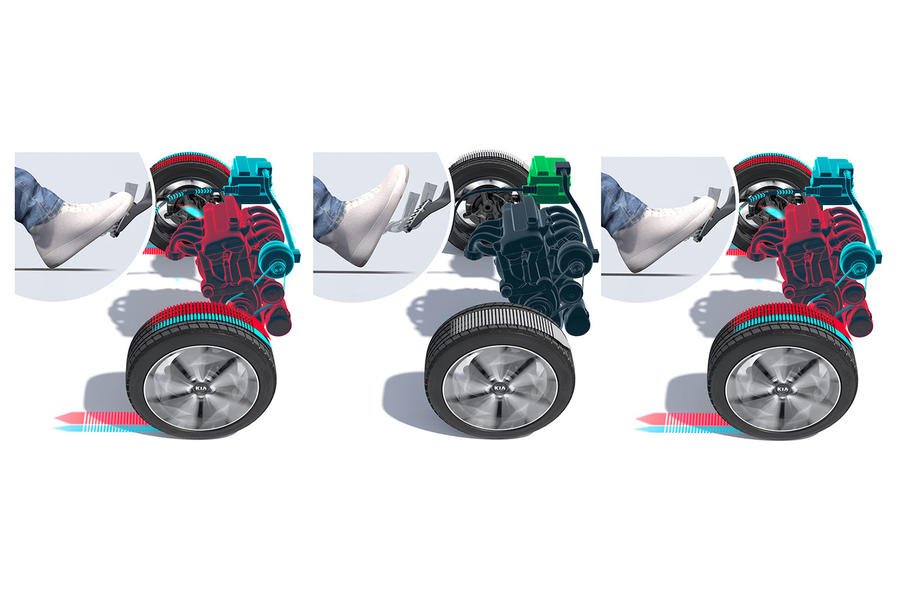

Clutches are normally operated in one of two ways: hydraulically or mechanically by a cable. A hydraulic system usually consists of master and slave cylinders. The master is attached to the clutch pedal, while the slave cylinder physically disengages the clutch. With the clutch-by-wire system, the clutch pedal sends a signal to an electronic control unit and an electrohydraulic actuator (replacing the conventional master cylinder) generates the hydraulic pressure. A slave cylinder opening the clutch is conventional.

Arguably, Kia has missed a trick in not opting for a completely 'dry' electromechanical system with an electrically operated clutch mechanism and no hydraulics, but that said, the chosen route could make packaging far more practical, especially in small cars, where nothing really needs to change in the design of the engine and gearbox. When the driver comes off the accelerator, either when cruising below 77mph or to slow down for the lights or a junction, coasting can give a modest effi ciency gain (Kia claims a CO2 reduction of 3%) by switching off the engine completely. There's no downhill coasting, though. When the driver brakes, the engine kicks back in to benefit from regenerative and engine braking.

During coasting, the system works as it would with an automatic gearbox: the clutch opens (but without the driver pressing the pedal), the engine shuts down and the car coasts with the car in gear. If the driver has a change of mind and presses the clutch pedal to select another gear, or gets back on the accelerator or brakes, the 48V starter-generator restarts the engine. In that case, the engine will resume drive with mild electrical assistance from the starter-generator if the car has slowed and the selected gear is a little too high. Once at a standstill at the lights, the system behaves much as it would with normal stop-start, restarting the engine when the driver presses the clutch or accelerator pedal.

A more environmentally sound tuk-tuk that's under development by UK firm DH2 can be literally home grown. The small, 480kg, low-voltage EV includes jute fibre-reinforced composites in its construction. Jute is readily available where the EV will be made and sold. Natural fibres are also under investigation by mainstream manufacturers for use in composite body panels.

Related News