West Virginia Researcher Describes How Volkswagen Got Caught

Excited by the prospect of breaking new ground, the team of two professors and two students wanted to gather as much data as possible. "And being academics, we went a little overboard," said Arvind Thiruvengadam, one of the students.

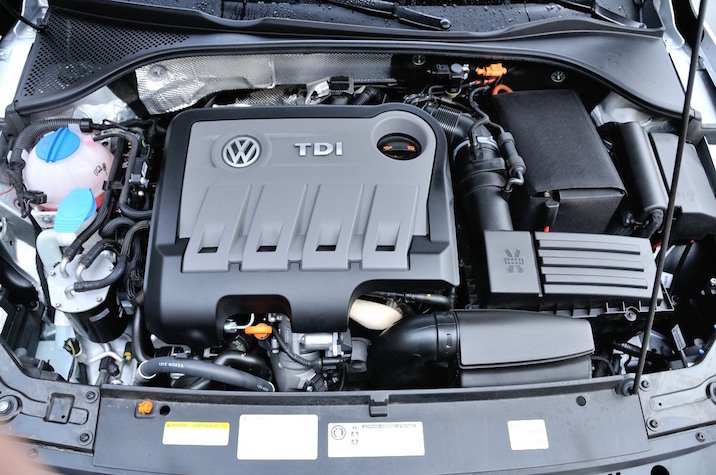

Overboard included driving the cars for more miles than they needed to test and verify results. Drivers put about 1,500 miles on each of the first two cars in the study, a Volkswagen Jetta and BMW X5, along California roadways. For their final car, a Volkswagen Passat, they wanted even more mileage. So they took the car on a road trip from Los Angeles to Seattle and back again, collecting data from more than 2,000 miles of testing.

The road trip was Volkswagen's undoing. When the West Virginia team returned to Los Angeles, they were befuddled by the test results. In theory, the Passat should have spewed the lowest levels of pollutants among the three cars. Equipped with the more modern selective catalytic reduction technology, the team expected to find minimal levels of nitrogen oxide. But the car, which had been certified at a California Air Resources Board facility prior to the start of the road trip, had elevated levels of NOx that were 20 times the baseline levels established beforehand.

The researchers, comprised of professors Gregory Thompson and Dan Carder and students Marc Besch and Thiruvengadam, knew their on-board equipment functioned properly because, early in their research, they had double-checked its accuracy after recording sky-high NOx readings from the Jetta that showed 30 times the level of its baseline testing at the CARB facility. It was particularly noteworthy because the Jetta contained the first-generation Lean NOx Trap technology, not the more efficient SCR, yet both produced large discrepancies. The BMW, on the other hand, performed as expected.

Today, Thiruvengadam is careful to say the research team never suspected Volkswagen of cheating on emissions testing, nor did the researchers report such a finding. They merely reported their findings to CARB officials who then further investigated. But the West Virginia team unpeeled the first layer of deception in a cheating scandal that has mushroomed in five short days, encompassing 11 million affected cars worldwide and ousting Volkswagen CEO Martin Winterkorn.

"Our due diligence had been done," Thiruvengadam tells Autoblog. "It wasn't that we tested three vehicles and brought down a corporation. Three vehicles is a very, very small subset of a half-million vehicles, so it was more that we had a role, the data we collected spoke for itself and CARB and EPA did their due diligence. We didn't point and say, 'Volkswagen has a defeat device.'"

On the contrary, after viewing the results, the researchers thought at the time perhaps Volkswagen had reached an agreement with the Environmental Protection Agency to use an auxiliary emissions control device for the vehicles, something they were familiar with from their frequent testing of heavy-duty vehicles at home. West Virginia's Center for Alternative Fuels Engines and Emissions specializes in emissions testing of heavy-duty equipment and diesels, and Thiruvengadam says such exemptions for specialty manufacturers are commonplace because manufacturers often swap different engines into a range of vehicles. But that theory didn't last long.

"When we see high emissions, we think maybe it's an AECD that's been negotiated," he said. "But even with an AECD, you wouldn't see it performing way better on a certification and then 30 times higher in the real world. That magnitude would never be there."

Perhaps they should have viewed the results with more skepticism. West Virginia studied the diesels' performances in partnership with the International Council on Clean Transportation, an international nonprofit organization dedicated to scientific and technical analysis of environmental regulations. The ICCT had conducted research in Europe and found significant gaps in the performance of diesels between certification testing and real-world results. Various tests in Rome and Milan had consistently found the gaps, which ICCT publicly identified in October 2014, and the discrepancies prompted them to follow-up with a study of diesels made by the European companies for the American market, in which they must meet stricter emissions standards. When ICCT commissioned the study, West Virginia submitted the winning bid for the project.

As other agencies unraveled the cheating scandal, Thiruvengadam countered his surprise that Volkswagen would stoop to deception with the ease at which it could be done. Although he hadn't analyzed the software algorithm that allowed Volkswagen's dishonest diesels to sense the presence of compliance testing, he said there were lots of ways an electronic control unit could be programmed to identify testing and change its fuel mapping toward low emission in those rare scenarios.

A car could sense when its hood is up for dynamometer testing, so a smart hood switch could double as a defeat device. Or a sensor could detect when traction control is disabled, another testing necessity, and send emission into an alternate mode. Or determine that the wheels are turning but the steering wheel is locked in one position. The possibilities are almost endless.

"Those things are very, very simple ones you can look at," said Thiruvengadam, who has graduated with his doctorate and now works as a research assistant professor at West Virginia. "I'm pretty sure that if you're one of the largest car manufacturers, you could do a lot more."

Related News