Are Half Of EV Owners Really 'Switching Back' To Gas? It's Complicated.

You probably saw the headlines. According to a new survey, 46% of electric vehicle owners in America now say they intend to "switch back" to internal combustion-powered cars. This particular statistic from McKinsey & Company's newest Mobility Consumer Pulse survey has been cited far and wide as an example of how troubled the EV transition really is.

The results go against conventional wisdom in the automotive world: That once people go electric, they almost never go back. Is that sentiment really starting to change right as the auto industry aims to take EVs more mainstream?

The reality is more complicated and nuanced than that, one of the study's authors told InsideEVs. And what the data proves, this author says, is that automakers, dealers and charging companies have a lot more work to do if they want to keep any sort of electric momentum going.

"It's important not to just get stuck on that headline," said Philipp Kampshoff, who leads McKinsey's Center for Future Mobility in the Americas. However, "when I look at the data, I think it's a bit of a clear warning signal that we need to fix these issues quickly," he said.

Who Switches Back?

The McKinsey study included a number of fascinating data points on what people think about autonomous driving functionalities, or whether they'd consider buying cars from China, or what they want from connected software features.

But a question about whether EV owners were "very likely" to switch back to ICE vehicles—meaning, replacing them entirely and not just adding a second or third gas or hybrid car to the fleet, Kampshoff said—has gotten the largest amount of wider attention. "We've gotten tons of inbound requests to talk about this one," he said.

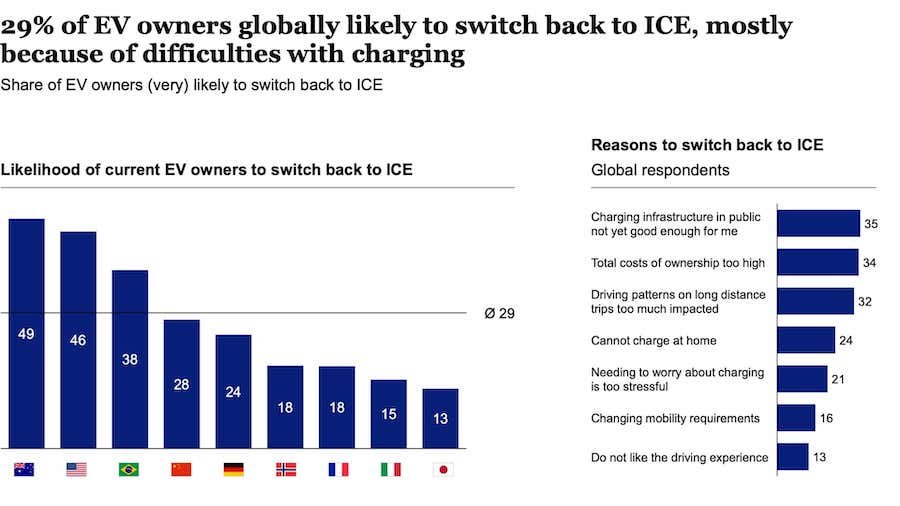

Globally, around 29% of the survey respondents said they probably would not go electric next time.

All of those owners cited familiar pain points with modern EVs: problems finding working public chargers, an inability to charge at home for whatever reason and general range anxiety.

Kampshoff said that the questionnaire went to about 36,000 people in 15 countries and that it was conducted in the last few months—meaning that it included a lot of new EV owners following a record year of global sales.

In the U.S., he said, that included about 4,000 respondents. In other words, only 1,840 people actually said they're likely to give up electric driving next time. That's a relative drop in the bucket, considering that about 1.4 million new EVs were registered in the U.S. in 2023 alone and many of those owners could be very happy with their purchases.

But the anti-EV sentiment among some drivers speaks to who is buying EVs now, and what new converts expect from the experience. And fixing those issues will be crucial to wider EV adoption, Kampshoff said.

Those new owners surveyed are, increasingly, moving away from the profile that long-defined the EV life: upper-income or wealthy, probably a single-family homeowner and probably buying a Tesla. Instead, they're buying from other brands at more affordable prices, often enticed by aggressive leasing and financing deals for EVs.

But that also means that they're living without Tesla's robust and reliable fast-charging network (until it's open to all drivers, anyway); may live in apartments without easy access to charging; and are less willing to put up with the kinds of EV-related headaches that many early adopters took in stride. And in recent years, going electric could mean losing a huge amount of your car's resale value thanks to last year's spate of price cuts, which Kampshoff said is another major turn-off for some current owners.

Interestingly, he said, many of those survey respondents in the U.S. who indicated they might reject EVs next time were on the younger side—around 36 years old. And many also have young families. They're the ones who have felt the pain of America's subpar charging network more than others, he said.

"Imagine having little children in the car and having to do a detour for half an hour to find a fast charger, and it's not working," Kampshoff said. "The frustration gets exacerbated."

Indeed, that's often an all-too-common situation for EV drivers, whether they have kids or not. Plus, charging at home remains difficult if you rent or live in an apartment complex. And while America's DC fast charging infrastructure has improved by leaps and bounds in recent years, it still struggles with both abundance and reliability.

"We're moving more and more into a generation of buyers that rely much on public charging infrastructure," Kampshoff said. "They probably use their car very similar to the way they've used a car before, just by going to public infrastructure. Before, you went to a gas station, and now you've got to use a charger. But now they're realizing, that's not so easy."

An Education Issue

Kampshoff said that this challenge is also an issue of education for buyers who are new to a technology that can be very different from gas-powered cars. Are they being told where and how to charge, or how to get a home charger if that's an option, or what a kilowatt-hour is and what it means for them?

But it's unclear who's going to step up and improve that situation. After all, many—but certainly not all—car dealers have been historically reluctant to sell EVs, since doing so comes with expensive charging investments and potentially losing out on repair revenue. And automakers have long relied on their "dealer partners" to teach customers about what these vehicles actually do. Plus, neither of those parties may be in a great rush to sell more EVs as they struggle to make and sell them profitably, he said.

"Not necessarily everybody is equally incentivized to sell them," he said. A dealer may say, "If you are unhappy with the infrastructure or residual values, why don't you switch back to an ICE car for now and then you can go back to your EV later?" he said. "Why not push those for a little longer?"

Still, Kampshoff said he was more optimistic about EVs after this study than you may think. "There's a lot of positive here," he said.

He said that since only 29% of global survey respondents indicated they would switch back to an ICE-powered vehicle instead of their EV, "You can make the statement that 71% said that they won’t switch back. That’s pretty high loyalty to EVs."

But more needs to be done by all parties involved to keep a new generation of buyers from fleeing electric cars next time.

"The reasons people are unsatisfied are not related to the product," he said. "They’re switching back because of charging and resale values. Both of those are fixable."

Nouvelles connexes