They will protest every time anyone dares to suggest any alternative that may help. I have already written about how these guys hate internal combustion engines (ICEs), so now I'll focus on their repulsion for hydrogen and fuel cells. As with ICEs, it is a matter of faith, not reason.

Before we take care of the hydrogen story, it is worth revisiting why ICEs may help. Those powered by biofuels and turned into electricity generators are the cheapest way to ensure BEVs will still travel as far as any vehicle powered solely by an engine.

These cars are called extended-range electric vehicles (EREVs). Still, several people prefer to call them plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), which is what they call anything that has an engine, an electric motor, and a battery pack that can be recharged. It becomes a bag of cats.

EREVs are powered solely by their motors, while PHEVs can also be propelled by their ICEs. Considering a vehicle that counts only on its motors to move is generally more efficient, having a different way to classify them is crucial.

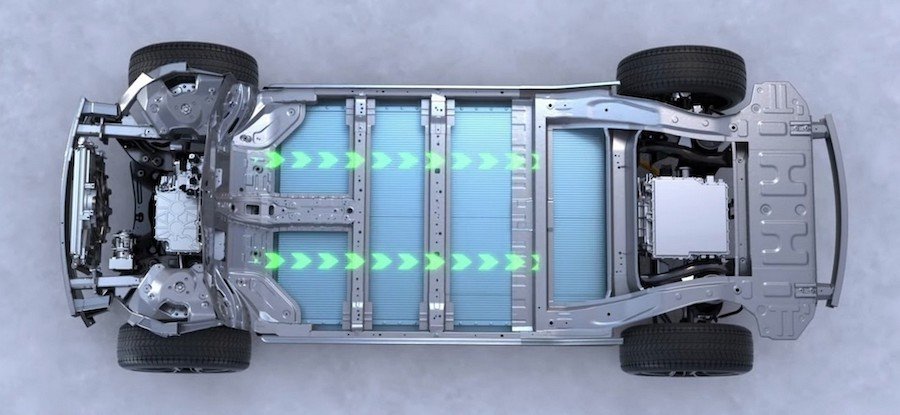

If you have an EREV powered by biofuels, it becomes an affordable option because it can have a small battery pack compared to those used by BEVs. Distributing this fuel is also cheap due to the infrastructure that gasoline and diesel already have. It is a matter of replacing the tanks. Charging stations for BEVs are more expensive to build and will service fewer customers, which makes its operation costs higher.

Hydrogen is pretty similar to fuels in the sense that you can refill a tank in less than five minutes. The fastest-charging BEVs currently for sale take four times as long, or at least 20 minutes, to go from 5% to 80% of state of charge (SoC). The issue is that this gas faces many hurdles, such as cost and distribution.

Owners of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) do not have many places where to buy the hydrogen they need. That leads to few people purchasing such cars. With low demand, entrepreneurs do not risk investing in hydrogen stations. It is a "chicken or the egg" dilemma that nobody managed to solve so far, even if there are interesting propositions on the table. But there's another crucial issue to solve.

Hydrogen is expensive nowadays, especially because most of it comes from natural gas. In 2023, Alexander Vlaskamp said it was four times as expensive as it would make sense for MAN's customers. The company's CEO did not mention the price, but a kilogram of hydrogen currently costs around $5.

All these problems can be solved, just like lithium-ion cells offered batteries a new hope. There are companies developing new methods of producing this gas from renewable sources and at much lower prices. Brazil is currently testing the idea of putting an ethanol reformer in an ordinary fuel station to deliver hydrogen to fuel cell vehicles. These are promising initiatives. None of that matters to BEV advocates.

They will stick their heads in the sand by arguing that it is ridiculous to spend electric energy making a gas that will generate electricity again. When you frame the whole thing this way, you will certainly be convinced that fuel cells are nonsense, but these guys always lack a crucial element of any analysis: context.

If storing electric energy in batteries were as convenient and fast as using hydrogen for that purpose, their reasoning would be bulletproof. But it isn't. They refuse to address how long it takes to charge a massive battery pack at home. Yet, they will say it is enough to travel or go to work. The deal is that cars have broader goals than taking people to school or work and back. And they are pretty expensive machines to have such limited goals.

When anyone goes on a road trip, they will need a way to get energy back as quickly as possible. For BEVs, there are only two options. Fast charging is the main one, but it deals with deadly high currents and is not that fast, as I already wrote in my article about ICEs. Battery swapping is much faster, but BEV advocates reject the idea. FCEVs are better equipped than BEVs to deal with traveling long distances due to their hydrogen tanks.

Imagine these FCEVs had smaller battery packs that you could still recharge at night at home, like EREVs or PHEVs. If these high-voltage accumulators were big enough for at least 62 miles (100 kilometers), that would help people run their daily errands purely on electricity. The hydrogen tanks would be used only as an energy backup.

Renault presented the concept car Scenic Vision with that proposition, and it instantly became the car I would like to buy – if it had LFP cells, which are safer than ternary units. Riversimple's network electric powertrain makes a lot of sense, as does its mobility-as-a-service business model. However, it has yet to present a car that would suit my needs, so I'd love to have a family EREV with a hydrogen tank and fuel cells.

Such a versatile car could even please those who hate the idea of using anything other than a battery pack. Should they need to travel further than they usually do, they could still fast-charge their vehicles, but the smaller battery pack would theoretically require less time to reach 80% SoC. It does not make sense, I know, but if BEV advocates would be happier that way...

In the end, if they are truly so worried about carbon emissions, why don't they accept burning carbon-neutral fuels, such as ethanol? Why don't they embrace hydrogen as a strategic power reserve? Putting hydrogen in combustion chambers is a waste when fuel cells can convert this gas into electricity with a much higher efficiency. Ask BEV advocates about this, and they will bash the idea as much as they mock any concept that is not the one they defend. It is as if their lives depended on it.

In the end, BEV advocates do not want a carbon-neutral society. They do not want to lower emissions as much as possible now. They just want the solution they have found to prevail above all others. Like religious fundamentalists, they just want to be right – and they definitely are not.

Nouvelles connexes